After Trump's silence over the Soleimani assassination, the UK faces a dilemma over its special relationship

It was embarrassing, even humiliating, that the British prime minister was not given notice of the American assassination of the Iranian general

There is an old African saying that, when elephants fight, it's the grass which suffers. Britain is feeling the discomfort of crushed grass as a result of the various fights picked by the government's powerful but belligerent friend Donald Trump.#

It was embarrassing, even humiliating, that the British prime minister was not given notice of the American strike against the Iranian general Qassem Soleimani. It isn't clear whether Trump didn't trust his British allies with confidential military intelligence, or didn't think we were important enough to merit a courtesy call. Either way, the snub was particularly galling, as 179 British troops have died supporting the Americans in Iraq.

If it were merely a case of loss of dignity, it wouldn't matter so much. Trump doesn't do courtesy, and perhaps we should appreciate his candour, making it clear that the special relationship is maybe special to Britain but isn't any longer special to the United States. But there are real British interests at stake.

The experience of UK ambassador Rob Macaire - arrested in Tehran and held for several hours - shows that even when the UK is behaving entirely properly, we are a target. Meanwhile, 400 British troops are involved in training the Iraqi army. They are at risk, as are many British civilians in and around the Gulf.

In Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, the Iranians effectively have a hostage, whose prison sentence can be lengthened or shortened as political circumstances demand. The Iranians are fully aware of Boris Johnson's inglorious role, undermining her trial defence. They will be alert for opportunities to apply leverage to an American ally with a military presence in the region.

As a nuclear weapons state, Britain also has a legal and political interest in non-proliferation, and in sustaining a nuclear agreement with Iran. Britain is closer to the European than the US position on Iran's compliance, or otherwise, with the previous agreement.

Anybody looking for clarity in this murky area should read Bob Woodward's chilling but also hilarious fly-on-the-wall account of life in the Trump White House. There is an episode where the then Secretary of State, Rex Tillerson, asks Trump to extend the agreement because of a lack of evidence of Iranian non-compliance. Trump insists that since he has decided to kill the agreement, there must - by definition - be non-compliance.

The UK now faces an awkward dilemma: defy the United States by trying to keep the agreement alive, or go along with inevitable pre-emptive strikes by the United States and/or Israel, which it will be alleged are essential to stop Iran acquiring nuclear weapons.

It may be that the Iran crisis will abate, for a while. There is, after all, some common ground. Iran wants United States troops out of the region, and Trump wants to get his troops out of the region. But there are far from trivial issues around honour, revenge and saving face. And if these emotions prevail over cold calculation, then British interests will be part of the collateral damage.

The same is true of the less violent, but ultimately more significant, dispute over trade, technology and security between the two superpowers: Trump's America and Xi Jinping's China. The current pause and likely truce in the escalating US-China trade war is probably just a temporary respite. It is easy to mock Trump's economically illiterate obsession with bilateral trade deficits. But he is serious about their elimination.

It is also true that there are wider and better grievances shared by many countries. China has been a free-rider on the liberal multilateral trading system gaining access to western markets and technology, while offering little by way of reciprocal access. The passive aggressive prickliness and the assertive nationalism of Xi regime adds fuel to the fire.

It's quite possible that the trade war will simmer rather than boil over in the next few months. The Chinese are smart enough to have realised that they can pursue their wider ambitions while offering Trump enough to meet his narrow concerns over the bilateral deficit. They may also be right to calculate that the president would prefer to shield Wall Street and the wider US economy from nasty economic shocks in an election year.

But for the UK, any hope of rich pickings at the other end of the Silk Road now looks forlorn. The "golden era" of Cameron and Osborne's love-in with the Chinese has long gone. The sensible and neat compromise proposed by Theresa May over Huawei - excluding the Chinese company from the most sensitive parts of new 5G networks but welcoming the competition and innovation they bring to other parts - is in grave jeopardy.

In the next few weeks, we shall be forced to make a final decision over Huawei, and the British will be told in no uncertain terms that they cannot risk being caught on the wrong side of the new iron curtain which will divide transformative technologies.

Of course, this is isn't the first time that the UK and USA have had divergent interests. Suez was one, Wilson's refusal to commit troops to Vietnam was another. Even Margaret Thatcher defied the United States over energy pipelines to the Soviet Union. But back then Britain still had some of the substance as well as the illusions of being a major player. Such a pretence is no longer credible. And we can no longer look to the European Union for political or diplomatic cover.

There will be a growing groundswell of support for those so-called neo-Cons who have long argued that our future is as a subordinate part of the Anglosphere. We should, they will say, accept and welcome our role on the back of one of the warring elephants, rather than being trampled underfoot. If that is the case, our future is as a transatlantic Canada without the French bits.

The Canadians will tell you that that isn't an easy existence, on matters of trade and many other things. But as we spurn Europe, it may be the best we can hope for.

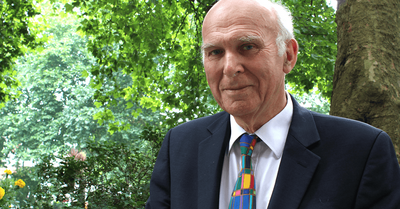

Sir Vince Cable is a former leader of the Liberal Democrats and a former secretary of state for business